Should you put your Theranos experience on your LinkedIn profile?

I reread John Carreyrou’s incredible 2018 book, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup, this summer with a board governance lens. But I kept thinking about all the exceptionally respected and established people, as well as university graduates in their first jobs, whose personal brands are (forever?) tied to the fraud.

I started looking up people mentioned in the book on LinkedIn to see where they are now. Did their affiliation crush their career paths? Did they turn lemons into lemonade? Did they just pretend it never happened? In doing so, I found a variety of ways people dealt with listing their experience.

Thousands of people worked there between 2003 and 2018. Obviously, not all of them were in on the fraud, and we know that many made efforts to speak up or quit when they figured out something was amiss. But knowing what we now know, is it better to have a multi-year hole in your work history, or hope that a potential employer understands enough about the situation to not hold it against you?

Whistleblowers Tyler Shultz and Erika Cheung have both spoken about how Theranos employees were forbidden to talk about their work and only allowed to put “Private Biotech Company” as their employer on LinkedIn. But the company has been shuttered for seven years now.

Theranos Heroes Leaned In

A sampling of profiles show an array of approaches to deal with their time at Theranos.

Erika Cheung, one of the heroes of the story, a whistleblower who filed a complaint with regulators in 2015, has made Theranos part of her origin story in the About Sectionm and since started a not-for-profit called Ethics in Entrepreneurship. But she still lists her seven months in 2013 and 2014 as a Laboratory Associate at a “Private Biotech Company.” I like to think this is intentionally cheeky.

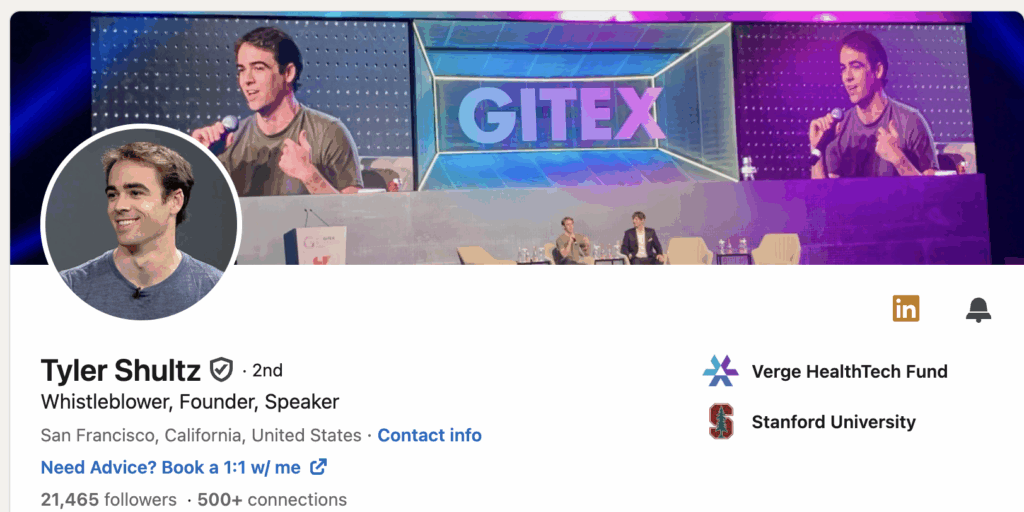

Tyler Shultz’s LinkedIn tag line is “Whistleblower, Founder, Speaker.” Talking about what he learned at Theranos has become part of his career. He identifies Theranos by name as his employer for the eight months he worked as a Research Engineer.

Ana Arriola-Kanada, a more minor figure in the book, clearly shows their four months in 2007 at Theranos as ‘Vice President, Chief Design Architect.’ The description starts with “Altruism through Corrupt Unethical Science-Fiction” and then proceeds to list their responsibilities, not-so-subtly pointing out that Larry Ellison and Don Lucas were backers (and also conned). They then include four links about the Theranos debacle that reference them, including the Carreyrou book. The section is written like someone holding their head high and getting on with it. And as their descriptor notes, ‘Chairwoman, Product & Engineering Leader. Creative. Formerly Microsoft, IDEO, Apple, Meta, PlayStation, Sony,’ they have done just that.

None of the above are people who, at least as portrayed in media accounts, have been blamed for what went on.

But what about some of the more senior employees whose hands look a little less clean in Carreyrou’s book? Daniel Young, who seems to have played point on gaslighting Shultz as the latter sought answers when he thought the company was playing fast and loose with its testing data, shows his Theranos time (nine years, from 2009 to 2018) without comment. He worked for himself until 2021, when AstraZeneca hired him. (Shultz relates his conversations with Young in detail in an audio book about his experience.)

On one hand, I’m surprised that Young is showing his time at Theranos on his LinkedIn profile. Spending nine years there, even if he did zero wrong, is a bad look at his level of seniority, to put it mildly. With a pretty generic name, he would have been very difficult to find on LinkedIn if he hadn’t listed Theranos. He could have slipped into digital obscurity.

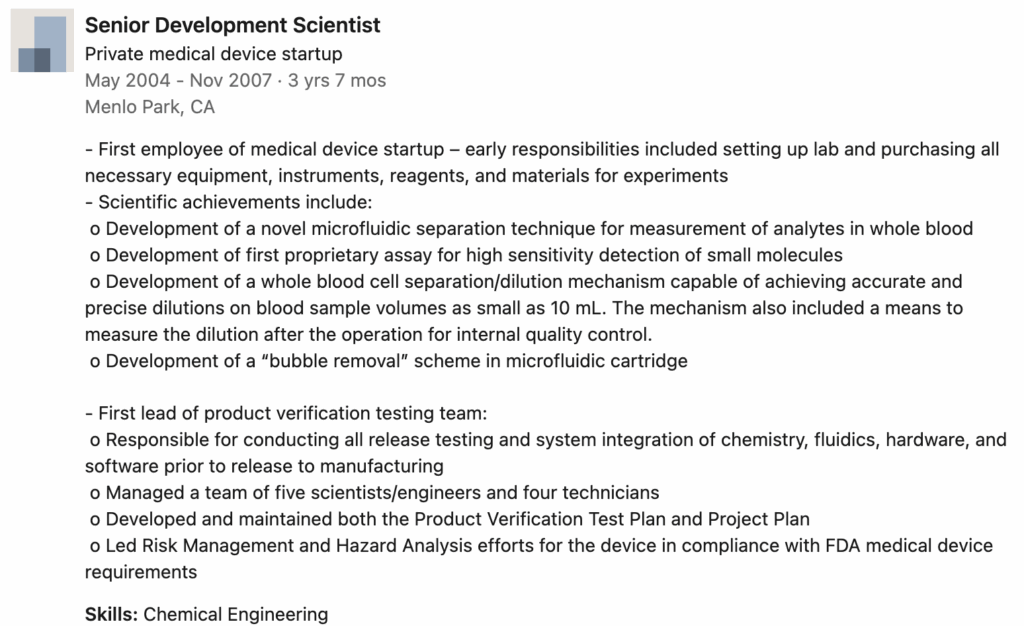

The eye-popping find was Shaunak Roy’s account. He calls himself the first employee of a “private medical device company.” Carreyrou, on the other hand, calls him a ‘co-founder,’ who started working with Holmes in Channing Robertson’s lab at Stanford. In Roy’s voluminous summary of his time at this “device company” from 2004 to 2007, he lists among his achievements “Development of a whole blood cell separation/dilution mechanism capable of achieving accurate and precise dilutions on blood sample volumes as small as 10 mL.”

Does Roy really believe that listing his Theranos ‘achievements’ boosts his profile almost 20 years later? In Carreyrou’s prologue, Roy’s reported to have told short-lived CFO Henry Mosley about the reliability of the Theranos device, “…You never knew whether you were going to get a result or not. So, they’d recorded a result from one of the times it worked. It was that recorded result that was displayed at the end of each demo.”

I couldn’t, incidentally, find a LinkedIn profile that was clearly that of the same ‘Mosley’ that worked at Theranos. There’s no trace of interviews with him, no reporting on court testimony, nothing that I could find that clearly ties him to Theranos. Perhaps he found another job after he was fired for speaking out and decided to keep his head down. Perhaps he retired or changed professions. But if he had aspirations for a CFO or CEO role at a public company, his lack of profile would have impeded that. As I often say, if you don’t exist on LinkedIn, you don’t exist in the business world.

But What Should I Do, Cheryl?

There’s no single rule to follow on whether to drop a stint at a problematic company from your LinkedIn profile. And Theranos is a special situation among special situations, in that the entire company was based on a lie, and has been shuttered for eight years.

But here are a few questions to filter whether to keep your experience with a scandalized brand on your LinkedIn profile.

- Did you know what was happening and do nothing? Is it reasonable to expect you should have?

- Did you get experience there that you need to demonstrate and can’t get anywhere else?

- Are you early in your career and thus don’t have much other experience to show?

- Is the company’s entire reputation wrapped up in the scandal? (E.g. people know about Enron’s collapse but also can easily understand that not everyone who worked there was wrapped up in the mess.)

- Was your name tightly woven into the narrative, so that an omission would look obvious and dishonest?

People assume that they are obligated to put all work experience into their LinkedIn profile. You do not. You can include as much or little experience as you like, and it does not have to be a duplication of your résumé.

Because LinkedIn is searchable and also ranks high in Google results, if you list a company that has been involved in a scandal (not just as an employer, but even as a client), you also risk having your name turn up for reporters when they are working on a story about the company or someone who worked there at the same time.

Regardless of your decision, know that even if you have a perfectly reasonable narrative about your involvement in a scandal, you may be weeded out from an opportunity by how you do or don’t address it on LinkedIn.